Fishless cycling is a fairly common practise in tropical fish aquaria where volumes of water are far smaller than in ponds and these smaller volumes allow aquarium enthusiasts to be able to quickly mature whole aquaria and their filters without fish being present.

Without fishless cycling, sensitive aquarium fish would be unable to tolerate the elevated levels of ammonia and nitrite that they would have experienced if they had been put into the tanks with an immature biofilter and had to wait until it matured. To understand fishless cycling, and how it differs from the more normal way to mature biofilters, it will first be necessary to understand what actually goes on in a biological filter as it matures.

The nitrogen cycle

Koi, in common with all fish, excrete ammonia as a waste product. This is a perfectly natural process and results from them needing protein in their diets. There are various forms of protein but all forms have one thing in common, they are made from substances called amino acids and amino acids are compounds based on ammonia.

When protein is metabolised, the ammonia compounds in it become a waste product and must be excreted.

Fortunately nitrifying bacteria have evolved to make use of the waste products of fish as a free energy resource. There are two main species of bug that are particularly suitable to do this in the pond environment. The ammonia bug (nitrosomonas) which will convert the ammonia into nitrite, and the nitrite bug (nitrobacter) which will convert that nitrite into nitrate. Neither does this as a favour to koi keepers, but if we make them a suitable home in our filter system, they will use these pollutants as an energy source that allows them to take up carbon from the surrounding water in order to grow and to multiply.

The natural maturation process

These bacteria are prolific in nature so if a pond is filled with new dechlorinated water and koi, or any form of aquatic life that excretes ammonia as its waste product is put into it, naturally occurring bacteria will soon be present in the water. They are primarily soil bacteria so they literally blow into new sources of water as spores which could be crudely thought of as being like bug "eggs". These bugs are so tiny that they might be carried into the pond on specks of dust blown by the wind. They are also present in the faeces of fish.

In view of that, the usual way to start up a biofilter is to provide a suitable media in a well aerated bay then release a small number of koi into the pond and wait. The fish are normally fed very lightly until the biofilter matures so that they will immediately begin releasing ammonia into the water. As soon as the first ammonia bug gets into the system it will begin to use the rising level of ammonia and start to multiply.

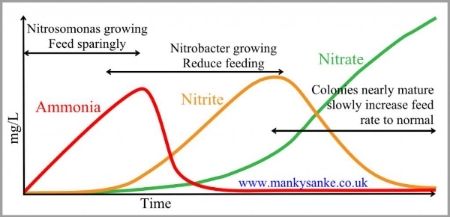

At first, the relatively small numbers of bugs that begin to populate the media will be unable to cope with all the ammonia from even a small number of small fish even if they are being fed very little and so ammonia levels will begin to rise as shown by the red ammonia curve.

As more and more ammonia is converted to nitrite by the ammonia bugs, the nitrite will become available as the energy source for the second colony of bacteria, the nitrite bug. Remember that these use nitrite as their energy source to allow them to take the carbon they need from their environment in order to grow and to multiply. Chemically, there is far less energy available in nitrite than in ammonia so the process of using it as their energy source is far less efficient which explains why the nitrite bug is weaker and grows more slowly than its cousin, the ammonia bug. This means that they multiply far more slowly and, even under good conditions, growing a full size nitrite bug colony will take several weeks. If ammonia levels rise too high during this natural maturing process, the rate at which they grow can be even slower because, although the nitrite bug actually needs a small amount of ammonia in its “diet” in addition to the large amount of nitrite that it uses, its reproductive processes are inhibited by high levels of ammonia.

During maturation, as the ammonia level rises and provides the energy for ammonia bugs, their growing colony size causes a growing level of their waste product, nitrite, as is shown by the orange curve and this doesn’t begin to decline until the nitrite bug colony has grown in size. When the nitrite bug colony is matured, they will be able to use all the available nitrite as quickly as the ammonia bug produces it and this produces a growing level of nitrate in the water. This nitrate isn’t quite as harmless to koi as was previously thought but, at least, it isn’t very toxic as long as levels are controlled by such means as water changes or special denitrifying media.

Maturing a pond biofilter without fish

When fish are used to supply the ammonia necessary to mature a biofilter, the process whereby, first the ammonia level rises then, as it falls, it is replaced by a longer lasting rising nitrite level until the biofilter has completely matured, is called new pond syndrome. With very limited numbers of fish on a very limited diet and with the help of water changes to keep the levels as low as is possible, the fish won’t be badly affected. However it’s difficult to keep levels within acceptable limits and this is the problem that fishless cycling is designed to eliminate.

Ammonia is ammonia and what is excreted by koi is no different to the household ammonia that we can buy in supermarkets except that koi excrete pure ammonia in small quantities whereas household ammonia is diluted to around 10% strength. Apart from this there is no difference at all so instead of using koi to supply the ammonia to mature media, ordinary household ammonia can be used instead. Fish are not required to be present and, indeed, they must not be present, so this gives rise to the name fishless cycling. With this method, the media can be matured in situ in one of the bays without the pump running (and with no fish in the pond yet) so that the volume of water that has to be dosed will only be the volume in that bay which is small in comparison with the volume of the pond. Or, if this is impractical, the media can be matured externally in a suitable container such as a dustbin.

Good quality houshold ammonia, that doesn’t have any extra additives to improve its effectiveness as a cleaning product, should be used. If the bottle doesn’t state exactly what it contains, a simple test is to shake it. Some bubbles will be formed and will quickly disperse but if shaking causes foaming which doesn’t disperse then the product will have extra additives which aren’t desirable.

The media should be matured either in pond water, if it is being matured in a biological bay, or in dechlorinated tap water if the process is being done externally. Air is essential. This will not only supply the oxygen the bugs will need but it will make sufficient currents in the water to keep it circulating within the bay or container, ensuring that the dissolved oxygen, the ammonia and the nitrite, when it eventually appears, are constantly being mixed and evenly distributed. Heating the water to around 20°C to 25°C with a small aquarium heater will help make the process quicker but isn’t essential if the water temperature is around 15°C or above.

Add carbon for growth

Since the sole reason for bacteria to dispose of ammonia or nitrite in our ponds is in order to allow them to assimilate carbon so that they can grow, a source of carbon needs to be added. There will usually be some form of carbonate in the water but the most convenient way to ensure that there is sufficient and that it is in the most suitable form is by adding 100 grams of sodium bicarbonate to the water before starting. It’s advisable to test the pH daily during the cycling process and add a little more sodium bicarbonate if it begins to show any tendency to fall. The precise pH isn’t important as long as it remains at a reasonably constant value between 7.0 and 8.5. It certainly shouldn’t be allowed to fall below 7.0 or the growing bacterial colonies will stop reproducing and may even be damaged but the suggested amount should be plenty so it’s unlikely to need topping up

The precise amount of ammonia to be added can be calculated according to the volume of water but the volume would need to be accurately measured beforehand and due allowance should be made for the volume of the media. If this is done, the correct dose rate will be 3 ml of 10% strength ammonia per 100 litres of water which will give an ammonia level of 3.0 mg/L. Alternatively for those who prefer not to do the maths, add half a teaspoon to the volume, measure the ammonia level this produces and add an extra appropriate amount. The precise level isn’t important but about 3 mg/L is a suitable level.

If this process is done in the open air, there won’t be any need to add any bacteria to seed the maturation because sufficient will land in the water by natural means but it could be significantly speeded up by adding a small quantity of matured media from a trusted source that is free of pathogens.

Test regularly

For the first week very little will happen but the ammonia level should be checked daily. Eventually the ammonia level will begin to fall. The nitrite level should then be checked daily along with the ammonia level and more ammonia added to keep the level at around 3 mg/L. As the ammonia level falls, there should be a corresponding rise in the nitrite level for at least a week, possibly two and then this rising level will also begin to fall.

The fishless cycling will be complete when all the ammonia added one day has completely gone by the following day leaving a near zero ammonia level and a near zero nitrite level. If the ammonia level is vanishing daily but the nitrite level persists, cut back on the amount of ammonia added so that the resultant nitrite level doesn’t become too high. As with the initial ammonia level, there are no hard and fast rules but the nitrite level should ideally be kept below around 5 mg/L. If this maximum can’t be managed by reducing the amount of ammonia added, it can be reduced by partial water changes of, say, 50%.

When the process is complete, all the water used in the biological bay must be dumped and the media lightly rinsed in dechlorinated water or pond water to remove any residual ammonia or nitrite. Once this is done the media will be ready for immediate use and should be returned to the filter system and the pond stocked as soon as is practical before the newly grown bacterial colonies begin to die back through lack of their nutrient supply.